The

Easie, True, and Genuine

NOTION

And Consistent

EXPLICATION

Of the NATURE of a

SPIRIT.

SECT. I.

The Opinions of the NULLIBISTS and HOLENMERIANS proposed.

THat we may explicate the Essence or Notion of Incorporeal Beings or Spirits, with the greater satisfaction and success, we are first to remove two vast Mounds of Darkness, wherewith the ignorance of some hath encumbred and obscured their nature.

And the first is of those who though they readily acknowledge there are such things as [100] Incorporeal Beings or Spirits, yet do very peremptorily contend that they are no where in the whole World. Which opinion, though at the very first sight it appears ridiculous, yet it is stiffly held by the maintainers of it, and that not without some Fastuosity and Superciliousness, or at least some more sly and tacite contempt of such Philosophers as hold the contrary, as of men less intellectual and too too much indulging to their Imagination. Those other therefore because they so boldly affirm that a Spirit is Nullibi, that is to say, Nowhere, have deservedly purchased to themselves the Name or Title of Nullibists.

The other Mound of Darkness laid upon the nature of a Spirit, is by those who willingly indeed acknowledge that Spirits are somewhere; but add further, That they are not onely entirely or totally in their whole Ubi or place, (in the most general sence of the word) but are totally in every part or point thereof, and describe the peculiar nature of a Spirit to be such, that it must be Totus in toto & totus in qualibet sui parte. Which therefore the Greeks would fitly and briefly call οὐσίαν ὀλενμερῆ, [an Essence that is all of it in each part] and this propriety thereof (τῶν ἀσωμάτων οὐτιῶν τὴν ὁλενμέρειαν) the Holenmerism of Incorporeal Beings. Whence also these other Philosophers diametrically opposite to the former, may most significantly and compendiously be called Holenmerians.

[101] SECT. II.

That Cartesius is the Prince of the Nullibists, and wherein chiefly consists the force of their Opinion.

THe Opinions of both which kind of Philosophers having sufficiently explained, we will now propose and confute the Reasons of each of them; and first of the Nullibists. Of whom the chief Author and Leader seems to have been that pleasant Wit Renatus Des Cartes, who by his jocular Metaphysical Meditations, has so luxated and distorted the rational Faculties of some otherwise sober and quick-witted persons, but in this point by reason of their over-great admiration of Des Cartes not sufficiently cautious, that deceived, partly by his counterfeit and prestigious subtilty, and partly by his Authority, have perswaded themselves that such things were most true and clear to them; which had they not been blinded with these prejudices, they could never have thought to have been so much as possible. And so they having been so industriously taught, and diligently instructed by him, how they might not be imposed upon, no not by the most powerful and most ill-minded fallacious Deity, have heed[102]lesly, by not sufficiently standing upon their guard, been deceived and illuded by a mere man, but of a pleasant and abundantly-cunning and abstruse Genius; as shall clearly appear after we have searched and examined the reasons of this Opinion of the Nullibists to the very bottom.

The whole force whereof is comprised in these three Axioms. The first, That whatsoever thinks is Immaterial, and so on the contrary. The second, That whatever is extended is Material. The third, That whatever is unextended is Nowhere. To which third <308> I shall add this fourth, as a necessary and manifest Consectary thereof, viz. That whatsoever is somewhere is extended. Which the Nullibists of themselves will easily grant me to be most true. Otherwise they could not seriously contend for their Opinion, whereby they affirm Spirits to be nowhere; but would be found to do it only by way of an oblique and close derision of their Existence, saying indeed they exist, but then again hiddenly and cunningly denying it, by affirming they are nowhere. Wherefore doubtlesly they affirm them to be nowhere, if they are in good earnest, for this reason onely; for fear they granting them to be somewhere, it would be presently extorted from them, even according to their own Principles, that they are extended, as whatever is Extended, is Material, according to their second Axiome. It [103] is therefore manifest that we both agree in this, that whatever real Being there is that is somewhere, is also Extended.

SECT. III.

The Sophistical weakness of that reasoning of the Nullibists, who, because we can conceive Cogitation without conceiving in the mean while Matter, conclude, That whatsoever thinks is Immaterial.

WIth which truth notwithstanding we being furnished and supported, I doubt not but we shall with ease quite overthrow and utterly root out this Opinion of the Nullibists. But that their levity and credulity may more manifestly appear, let us examine the Principles of this Opinion by parts, and consider how well they make good each member.

The first is, Whatever thinks is Immaterial, and on the contrary. The conversion of this Axiome I will not examine, because it makes little to the present purpose. I will onely note by the by, that I doubt not but it may be false, although I easily grant the Axiome itself to be true. But it is this new Method of demonstrating it I call into question, which from hence, that we can conceive Cogitation, in the [104] mean time not conceiving Matter, concludes that Whatever thinks is Immaterial. Now that we can conceive Cogitation without conceiving Matter, they say is manifest from hence, That although one should suppose there were no Body in the Universe, and should not flinch from that position, yet notwithstanding he would not cease to be certain, that there was Res cogitans, a thinking Being, in the World, he finding himself to be such. But I further add, though he should suppose there was no Immaterial Being in nature, (nor indeed Material) and should not flinch from that position, yet he would not cease to be certain that there was a thinking Being, (no not if he should suppose himself not to be a thinking Being) because he can suppose nothing without Cogitation. Which I thought worth the while to note by the by, that the great levity of the Nullibists might hence more clearly appear.

But yet I add further, that such is the nature of the Mind of man, that it is like the Eye, better fitted to contemplate other things than itself; and that therefore it is no wonder that thinking nothing of its own Essence, it does fixedly enough and intently consider in the mean time and contemplate all other things, yea, those very things with which she has the nearest affinity, and yet without any reflection that herself is of the like nature. [105] Whence it may easily come to pass, when she is so wholly taken up in contemplating other things without any reflection upon herself, that either carelesly she may consider herself in general as a mere thinking Being, without any other Attribute, or else by resolvedness afterwards, and by a force on purpose offered to her own faculties. But that this reasoning is wonderfully weak and trifling as to the proving of the Mind of man to be nothing else; that is to say, to have no other Attributes but mere Cogitation, there is none that does not discern.

SECT. IV.

The true Method that ought to be taken for the proving that MATTER cannot think.

LAstly, if Cartesius with his Nullibists would have dealt bona fide, they ought to have omitted all those ambagious windings and Meanders of feigned Abstraction, and with a direct stroke to have faln upon the thing itself, and so to have sifted Matter, and searched the nature of Cogitation, that they might thence have evidently demonstrated that there was some inseparable Attribute in Matter that is repugnant to the Cogitative faculty, or in Cogitation that is repugnant to Matter. But out [106] of the mere diversity of Idea's or Notions of any Attributes, to collect their separability or real distinction, yea their contrariety and repugnancy, is most foully to violate the indispensable Laws of Logick, and to confound Diversa with Opposita, and make them all one. Which mistake to them that understand Logick must needs appear very coarse and absurd.

But that the weakness and vacillancy of this Method may yet more clearly appear, let us suppose that which yet Philosophers of no mean name seriously stand for and assert, viz. That Cogitative substance is either Material or Immaterial; does it not apparently follow thence, that a thinking substance may be precisely conceived without the conception of Matter, as Matter without the conception of Cogitation, when notwithstanding in one of the members of this distribution they are joyned sufficiently close together?

How can therefore this newfangled Method of Cartesius convince us that this Supposition is false, and that the distribution is illegitimate? Can it from thence, that Matter may be conceived without Cogitation, and Cogitation without Matter? The first all grant, and the other the distribution itself supposes; and yet continues sufficiently firm and sure. Therefore it is very evident, that there is a necessity of our having recourse to the known and ra[107]tified Laws of Logick, which many Ages before this new upstart Method of Des Cartes appeared, were established and approved by the common suffrage of Mankind; Which teach us <309> that in every legitimate distribution the parts ought consentire cum toto, & dissentire inter se, to agree with the Whole, but disagree one with another. Now in this Distribution that they do sufficiently disagree, it is very manifest. It remains onely to be proved, that one of the parts, namely that which supposes that a Cogitative substance may be Material, is repugnant to the nature of the Whole. This is that clear, solid and manifest way or method according to the known Laws of Logick; but that new way, a kind of Sophistry and pleasant mode of trifling and prevaricating.

SECT. V.

That all things are in some sort extended, demonstrated out of the Corollary of the third Principle of the Nullibists,

AS for the second Axiome or Principle, viz. That whatsoever is extended is Material; for the evincing the falsity thereof, there want no new Arguments, if one have but recourse to the Sixth, Seventh, and Eighth Chapters of Enchiridium Metaphysicum, where by unan[108]swerable reasonings it is demonstrated, That there is a certain Immaterial and Immovable Extensum distinct from the movable Matter. But however, out of the Consectary of their third Principle, we shall prove at once, that all Spirits are Extended as being somewhere, against the wild and ridiculous Opinion of the Nullibists.

Whose third Principle, and out of which immediately and precisely they conclude Spirits to be nowhere, is, Whatsoever is unextended is nowhere. Which I very willingly grant; but on this condition, that they on the other side concede (and I doubt not but they will) That whatsoever is somewhere is also extended; from which Consectary I will evince with Mathematical certainty, That God and our Soul, and all other Immaterial Beings, are in some sort extended: For the Nullibists themselves acknowledge and assert, that the Operations wherewith the Soul acts on the Body, are in the Body; and that Power or Divine Vertue wherewith God acts on the Matter and moves it, is present in every part of the Matter. Whence it is easily gathered, That the Operation of the Soul and the moving Power of God is somewhere, viz. in the Body, and in the Matter. But the Operation of the Soul wherewith it acts on the Body and the Soul itself, and the Divine Power wherewith God moves the Matter and God himself, are together, nor can [109] so much as be imagined separate one from the other; namely, the Operation from the Soul, and the Power from God. Wherefore if the Operation of the Soul is somewhere, the Soul is somewhere, viz. there where the Operation. And if the Power of God be somewhere, God is somewhere, namely, there where the Divine Power is; He in every part of the Matter, the Soul in the humane Body. Whosoever can deny this, by the same reason he may deny that common Notion in Mathematicks, Quantities that are singly equal to one third, are equal to one another.

SECT. VI.

The apert confession of the Nullibists that the ESSENCE of a Spirit is where its OPERATION is; and how they contradict themselves, and are forced to acknowledge a Spirit extended.

ANd verily that which we contend for, the Nullibists seem apertly to assert, even in their own express words, as it is evident in Lambertus Velthusius in his De Initiis Primæ Philosophiæ, in the Chapter De Ubi. Who though he does manifestly affirm that God and the Mind of man by their Operations are in every part or some one part of the Matter; [110] and that in that sence, namely, in respect of their Operations, the Soul may be truly said to be somewhere, God everywhere; as if that were the onely mode of their presence: yet he does expresly grant that the Essence is nowhere separate from that whereby God or a created Spirit is said to be, the one everywhere, the other somewhere; that no man may conceit the Essence of God to be where the rest of his Attributes are not. That the Essence of God is in Heaven, but that his Vertue diffuses itself beyond Heaven. No by no means, saith he, Wheresoever God's Power or Operation is, there is the Nature of God; forasmuch as God is a Substance devoid of all composition. Thus far Velthusius. Whence I assume, But the Power or Operation of God is in or present to the Matter, Therefore the Essence of God is in or present to the Matter, and is there where the Matter is, and therefore somewhere. Can there be any deduction or illation more close and coherent with the Premises?

And yet that other most devoted follower of the Cartesian Philosophy, Ludovicus De-la-Forge, cannot abstain from the offering us the same advantage of arguing, or rather from the inferring the same conclusion with us, in his Treatise De Mente Humana, Chap. 12. where occur these words: Lastly, when I say that God is present to all things by his Omnipotency, (and consequently to all the parts of [111] the Matter) I do not deny but that also by his Essence or Substance he is present to them: For all those things in God are one and the same.

Dost thou hear, my Nullibist, what one of the chiefest of thy Condisciples and most religious Symmists of that stupendious secret of Nullibism plainly professes, namely, that God is present to all the parts of Matter by his Essence also, or Substance? And yet you in the mean while blush not to assert, that neither God nor any created spirit is any where; than which nothing more contradictious can be spoke or thought, or more abhorring from all reason. Wherefore whenas the Nullibists come so near to the truth, it seems impossible they should, so all of a suddain, start from it, unless they were blinded with a superstitious admiration of Des Cartes his Metaphysicks, and were deluded, effascinated and befooled with his jocular Subtilty and prestigious Abstractions there: <310> For who in his right wits can acknowledge that a Spirit by its Essence may be present to Matter and yet be nowhere, unless the Matter were nowhere also? And that a Spirit may penetrate, possess, and actuate some determinate Body, and yet not be in that Body? In which if it be, it is plainly necessary it be somewhere.

And yet the same Ludovicus De-la-Forge does manifestly assert, that the Body is thus [112] possest and actuated by the Soul, in his Preface to his Treatise De Mente Humana, while he declares the Opinion of Marcilius Ficinus concerning the manner how the Soul actuates the Body in Marsilius his own words, and does of his own accord assent to his Opinion. What therefore do these Forms to the Body when they communicate to it their Esse? They throughly penetrate it with their Essence, they bequeath the Vertue of their Essence to it. But now whereas the Esse is deduced from the Essence, and the Operation flows from the Vertue, by conjoyning the Essence they impart the Esse, by bequeathing the Vertue they communicate the Operations; so that out of the congress of Soul and Body, there is made one Animal Esse, one Operation. Thus he. The Soul with her Essence penetrates and pervades the whole Body, and yet is not where the Body is, but nowhere in the Universe!

With what manifest repugnancy therefore to their other Assertions the Nullibists hold this ridiculous Conclusion, we have sufficiently seen, and how weak their chiefest prop is, That whatever is Extended is Material; which is not onely confuted by irrefragable Arguments, Chap. 6, 7, and 8. Enchirid. Metaphys. but we have here also, by so clearly proving that all Spirits are somewhere, utterly subverted it, even from that very Concession or Opinion of the Nullibists themselves, who concede or aver [113] that whatsoever is somewhere is extended. Which Spirits are and yet are not Material.

SECT. VII.

The more light reasonings of the Nullibists whereby they would confirm their Opinion. The first of which is, That the Soul thinks of those things which are nowhere.

BUt we will not pass by their more slight reasonings in so great a matter, or rather so monstrous. Of which the first is, That the Mind of man thinks of such things as are nowhere, nor have any relation to place, no not so much as to Logical place or Ubi. Of which sort are many truths as well Moral as Theological and Logical, which being of such a nature that they are nowhere, the Mind of man which conceives them is necessarily nowhere also. But how crazily and inconsequently they collect that the humane Soul is nowhere, for that it thinks of those things that are nowhere, may be apparent to any one from hence, and especially to the Nullibists themselves; because from the same reason it would follow that the Mind of man is somewhere, because sometimes, if not always in a manner, it thinks of those things which are somewhere, as all Material things are. Which yet they [114] dare not grant, because it would plainly follow from thence, according to their Doctrine, that the Mind or Soul of man were extended, and so would become corporeal and devoid of all Cogitation. But besides, These things which they say are nowhere, namely, certain Moral, Logical, and Theological Truths, are really somewhere, viz. in the Soul itself which conceives them; but the Soul is in the Body, as we proved above. Whence it is manifest that the Soul and those Truths which she conceives are as well somewhere as the Body itself. I grant that some Truths as they are Representations, neither respect Time nor Place in whatever sence. But as they are Operations, and therefore Modes of some Subject or Substance, they cannot be otherwise conceived than in some substance. And forasmuch as there is no substance which has not some amplitude, they are in a substance which is in some sort extended; and so by reason of their Subject they are necessarily conceived to be somewhere, because a Mode is inseparable from a Subject.

Nor am I at all moved with that giddy and rash tergiversation which some betake themselves to here, who say we do not well in distinguishing betwixt Cogitation (such as are all conceived verities) and the Substance of the Soul cogitating: For Cogitation itself is the very Substance of the Soul, as Extension is of [115] Matter; and that therefore the Soul is as well nowhere as any Cogitation, which respects neither time nor place, would be, if it were found in no Subject. But here the Nullibists, who would thus escape, do not observe that while they acknowledge the Substance of the Soul to be Cogitation, they therewithal acknowledge the Soul to have a Substance, whence it is necessary it have some amplitude. And besides, This Assertion whereby they assert Cogitation to be the very substance of the Soul, is manifestly false. For many Operations of the Soul, are, as they speak, specifically different; Which therefore succeeding one after another, will be so many Substances specifically different. And so the Soul of Socrates will not always be the same specifical Soul, and much less the same numerical; Than which what can be imagined more delirant, and more remote from common sense?

To which you may adde, That the Soul of man is a permanent Being, but her Cogitations in a flux or succession; How then can the very substance of the Soul be its successive Operations? And when the substance of the Soul does so perpetually cease or perish, what I beseech you will become of Memory? From whence it is manifestly evident, that there is a certain permanent Substance of the Soul, as much distinct or different from her succeeding Cogitations, as the Matter itself is from its successive figures and motions.

<311> [116] SECT. VIII.

The second reason of the Nullibists, viz. That COGITATION is easily conceived without EXTENSION.

THe second Reason is somewhat coincident with some of those we have already examined; but it is briefly proposed by them thus: There can be no conception, no not of a Logical Place, or Ubi, without Extension. But Cogitation is easily conceived without conceiving any Extension: Wherefore the Mind cogitating, exempt from all Extension, is exempt also from all Locality whether Physical or Logical; and is so loosened from it, that it has no relation nor applicability thereto; as if those things had no relation nor applicability to other certain things without which they might be conceived.

The weakness of this argumentation is easily deprehended from hence, That the Intensness of heat or motion is considered without any respect to its extension, and yet it is referred to an extended Subject, viz. To a Bullet shot, or red hot Iron. And though in intent and defixed thoughts upon some either difficult or pleasing Object, we do not at all observe how the time passeth, nor take the [117] slightest notice of it, nothing hinders notwithstanding but those Cogitations may be applied to time, and it be rightly said, that about six a clock, suppose, in the Morning they began, and continued till eleven; and in like manner the place may be defined where they were conceived, viz. within the Walls of such an ones Study, although perhaps all that time this so fixt Contemplator did not take notice whether he was in his Study or in the Fields.

And to speak out the matter at once, From the precision of our thoughts to infer the real precision or separation of the things themselves, is a very putid and puerile Sophism; and still the more enormous and wilde, to collect also thence, that they have no relation nor applicability one to another. For we may have a clear and distinct apprehension of a thing which may be connected with another by an essential Tye, that Tye being not taken notice of, (and much more when they are connected onely with a circumstantial one) but not a full and adequate apprehension, and such as sees through and penetrates all the degrees of its Essence with their properties; Which unless a man reach to, he cannot rightly judge of the real separability of any nature from other natures.

From whence it appears how foully Cartesius has imposed, if not upon himself, at least upon others, when from this mental precision [118] of Cogitation from Extension, he defined a Spirit (such as the humane Soul) by Cogitation onely, Matter by Extension, and divided all Substance into Cogitant and Extended, as into their first species or kinds. Which distribution notwithstanding is as absonous and absurd, as if he had distributed Animal into Sensitive and Rational. Whenas all Substance is extended as well as all Animals sensitive. But he fixed his Animadversion upon the specifick nature of the humane Soul; the Generical nature thereof, either on purpose or by inadvertency, being not considered nor taken notice of by him, as hath been noted in Enchiridion Ethicum, lib. 3. cap. 4. sect. 3.

SECT. IX.

The third and last Reason of the Nullibists, viz. That the Mind is conscious to herself, that she is nowhere, unless she be disturbed or jogged by the Body.

THe third and last Reason, which is the most ingenious of them all, occurs in Lambertus Velthusius, viz. That it is a truth which God has infused into the Mind itself, That she is nowhere, because we know by experience that we cannot tell from our spiritual Operations where the Mind is. And for that [119] we know her to be in our Body, that we onely perceive from the Operations of Sense and Imagination, which without the Body or the motion of the Body the Mind cannot perform. The sence whereof, if I guess right, is this; That the Mind by a certain internal sense is conscious to herself that she is nowhere, unless she be now and then disturbed by the motions or joggings of the Body; which is, as I said, an ingenious presage, but not true: For it is one thing to perceive herself to be nowhere, another not to perceive herself to be somewhere. For she may not perceive herself to be somewhere, though she be somewhere, as she may not take notice of her own Individuality, or numerical Distinction, from all other minds, although she be one Numerical or Individual mind distinct from the rest: For, as I intimated above, such is the nature of the mind of man, that like the eye, it is better fitted for the contemplating all other things, than for contemplating itself. And that indeed which is made for the clearly and sincerely seeing other things, ought to have nothing of itself actually perceptible in it, which it might mingle with the perception of those other things. From whence the Mind of man is not to have any stable and fixt sense of its own Essence; and such as it cannot easily lay aside upon occasion: And therefore it is no wonder, whenas the Mind of man can put off the sense and [120] consciousness to itself of its own Essence and Individuality, that it can put off also therewith the sense of its being somewhere, or not perceive it; whenas it does not perceive its own Essence and Individuality, (of which Hic & Nunc are the known Characters:) And the chief Objects of the Mind are Universals.

But as the Mind, although it perceives not its Individuality, yet can by reason prove to herself that she is some one Numerical or Individual Mind, so she can by the same means, although she by inward sense perceives not where she is, evince notwithstanding that she is somewhere, from the general account of things, which have that of their own nature, that they are extended, singular, and somewhere. And besides, Velthusius <312> himself does plainly grant, that from the Operations of Sense and Imagination, we know our Mind to be in our Body. How then can we be ignorant that she is somewhere, unless the Body itself be nowhere?

[121] SECT. X.

An Appeal to the internal sense of the Mind, if she be not environed with a certain infinite Extension; together with an excitation of the Nullibist out of his Dream, by the sound of Trumpeters surrounding him.

THe Reasons of the Nullibists whereby they endeavour to maintain their Opinion, are sufficiently enervated and subverted. Nor have we need of any Arguments to establish the contrary Doctine. I will onely desire by the by, that he that thinks his Mind is nowhere, would make trial of his faculty of Thinking; and when he has abstracted himself from all thought or sense of his Body, and fixed his Mind onely on an Idea of an indefinite or infinite Extension, and also perceives himself to be some particular cogitant Being, let him make trial, I say, whether he can any way avoid it, but he must at the same time perceive that he is somewhere, namely, within this immense Extension, and that he is environ'd round about with it. Verily, I must ingenuously confess, that I cannot conceive otherwise, and that I cannot but conceive an Idea of a certain Extension infinite and immovable, and of necessary and actual Existence: Which I [122] most clearly deprehend, not to have been drawn in by the outward sense, but to be innate and essentially inherent in the Mind itself; and so to be the genuine object not of Imagination, but of Intellect; and that it is but perversly and without all judgement determined by the Nullibists, or Cartesians, that whatever is extended, is also φανταστόν τι or the Object of Imagination; When notwithstanding there is nothing imaginable, or the Object of Imagination, which is not sensible: For all Phantasms are drawn from the senses. But this infinite Extension has no more to do with things that are sensible and fall under Imagination, than that which is most Incorporeal. But of this haply it will be more opportune to speak elsewhere.

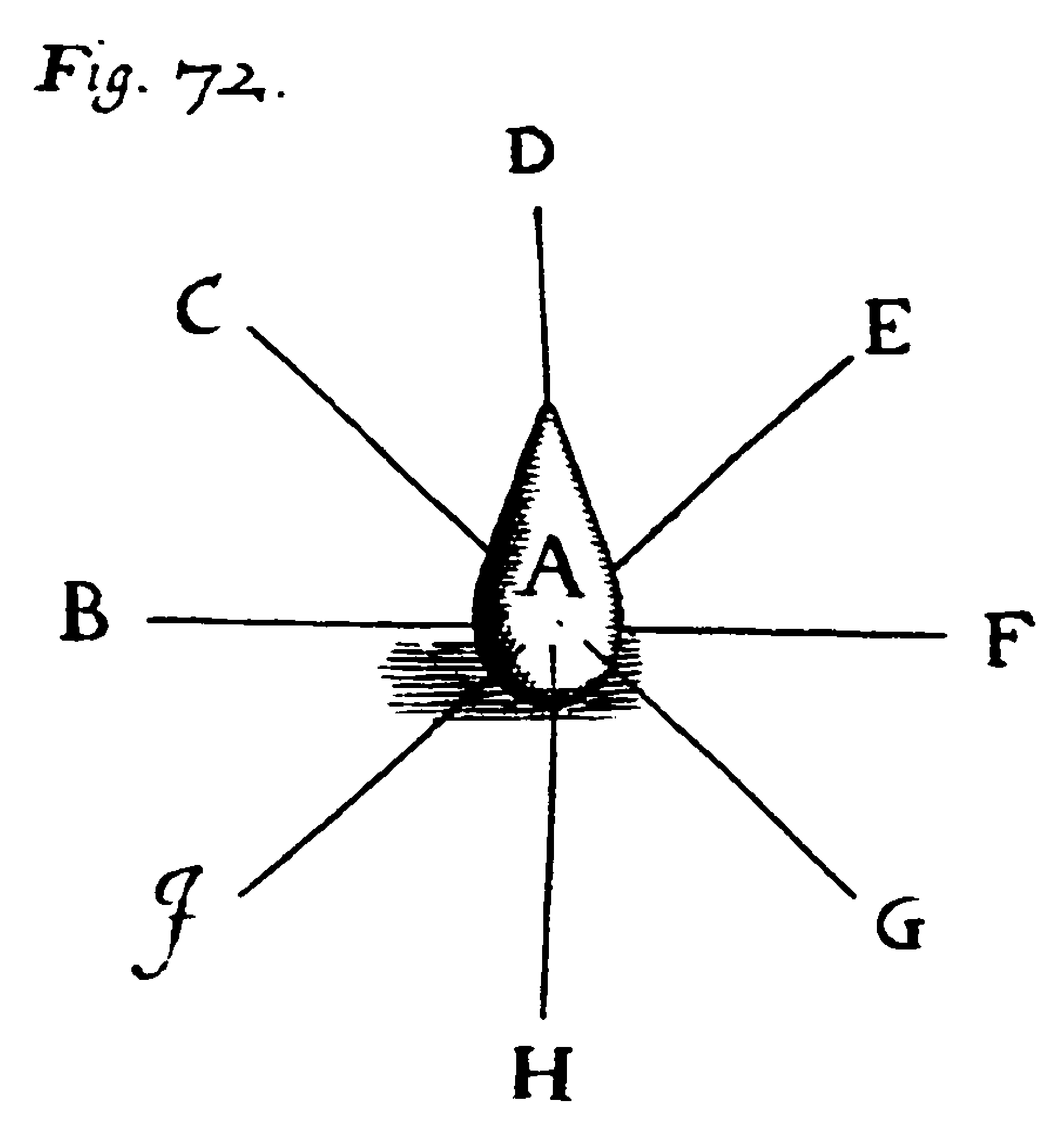

In the mean time I will subjoyn onely one Argument, whereby I may manifestly evince that the Mind of man is somewhere, and then I will betake my self to the discussing of the Opinion of the Holenmerians. Briefly therefore let us suppose some one environed with a Ring of Trumpeters, and that they all at the same time sound their Trumpets. Let us now see if the circumsonant clangor of those surrounding Trumpets sounding from all sides will awake these Nullibists out of their Lethargick Dream. And let us suppose, which they will willingly concede, that the Conarion or Glandula Pinealis, A, is the seat of the com[123]mon sense, to which at length all the motions from external Objects arrive. Nor is it any matter whether it be this Conarion, or some other part of the Brain, or of what is contained in the Brain: But let the Conarion, at least for this bout, supply the place of that matter which is the common Sensorium of the Soul.

And whenas it is supposed to be surrounded with Eight Trumpeters, let there be Eight Lines drawn from them, namely, from B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I; I say that the clangour or sound of every Trumpet is carried from the Ring of the Trumpeters to the extream part [124] of every one of those Lines, and all those sounds are heard as coming from the Ring B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, and perceived in the Conarion A; and that the perception is in that part to which all the Lines of motion, as to a common Centre, do concur; and therefore the extream parts of them, and the perceptions of the Clangours or Sounds, are in the middle of the Ring of Trumpeters, viz. where the Conarion is: Wherefore the Percipient itself, namely the Soul, is in the midst of this Ring as well as the Conarion, and therefore is somewhere. Assuredly he that denies that he conceives the force of this Demonstration, and acknowledges that the Perception indeed is at the extream parts of the said Lines, and in the middle of the Ring of Trumpeters, but contends in the mean time that the Mind herself is not there, forasmuch as she is nowhere; this man certainly is either delirant and crazed, or else plays tricks, and slimly and obliquely insinuates that the perception which is made in the Conarion is to be attributed to the Conarion itself; and that the Mind, so far as it is conceived to be an Incorporeal Substance, is to be exterminated out of the Universe, as an useless Figment and Chimæra.

And whenas it is supposed to be surrounded with Eight Trumpeters, let there be Eight Lines drawn from them, namely, from B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I; I say that the clangour or sound of every Trumpet is carried from the Ring of the Trumpeters to the extream part [124] of every one of those Lines, and all those sounds are heard as coming from the Ring B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, and perceived in the Conarion A; and that the perception is in that part to which all the Lines of motion, as to a common Centre, do concur; and therefore the extream parts of them, and the perceptions of the Clangours or Sounds, are in the middle of the Ring of Trumpeters, viz. where the Conarion is: Wherefore the Percipient itself, namely the Soul, is in the midst of this Ring as well as the Conarion, and therefore is somewhere. Assuredly he that denies that he conceives the force of this Demonstration, and acknowledges that the Perception indeed is at the extream parts of the said Lines, and in the middle of the Ring of Trumpeters, but contends in the mean time that the Mind herself is not there, forasmuch as she is nowhere; this man certainly is either delirant and crazed, or else plays tricks, and slimly and obliquely insinuates that the perception which is made in the Conarion is to be attributed to the Conarion itself; and that the Mind, so far as it is conceived to be an Incorporeal Substance, is to be exterminated out of the Universe, as an useless Figment and Chimæra.

[125] SECT. XI.

The Explication of the Opinion of the Holenmerians, together with their Two Reasons thereof proposed.

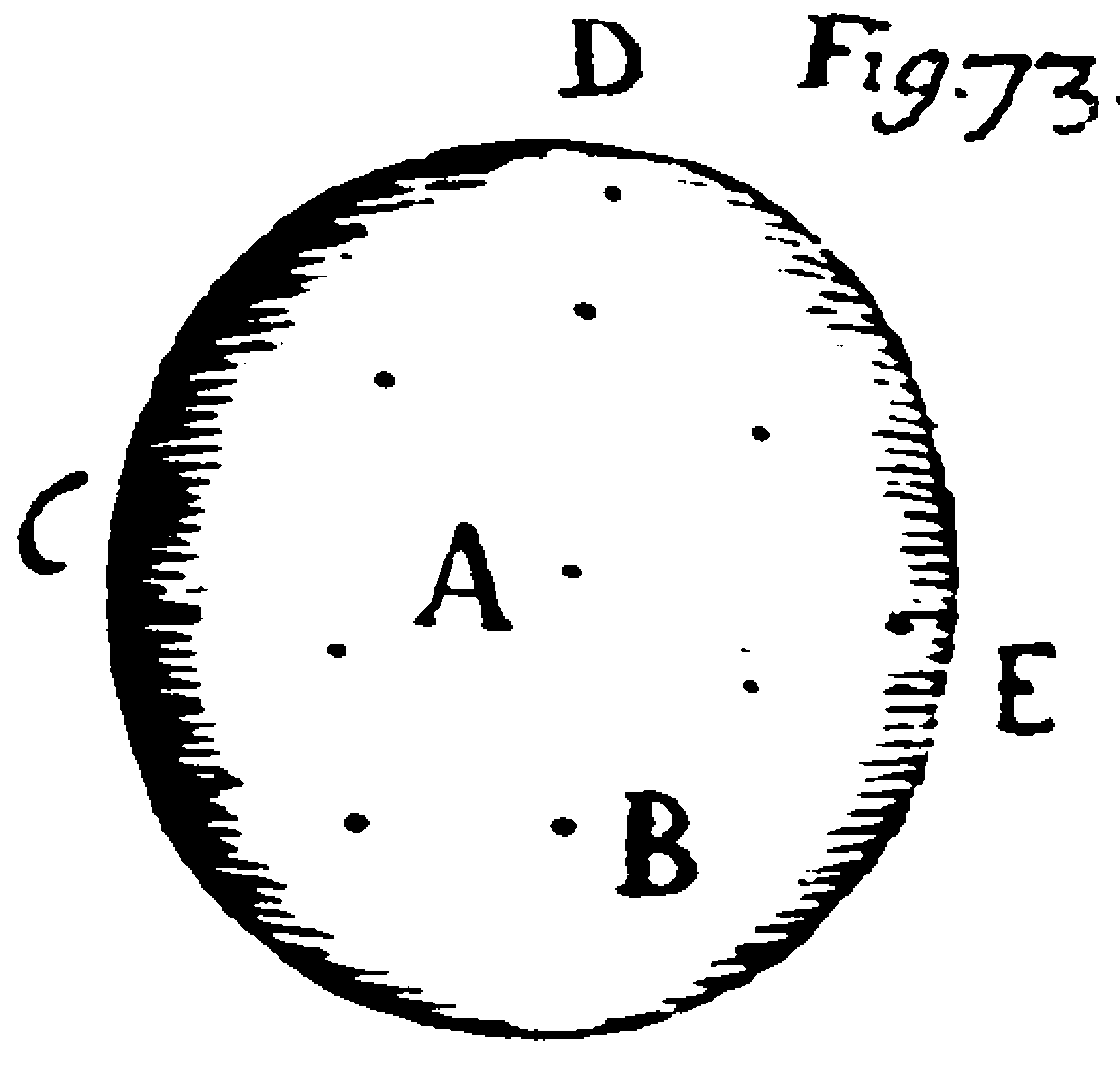

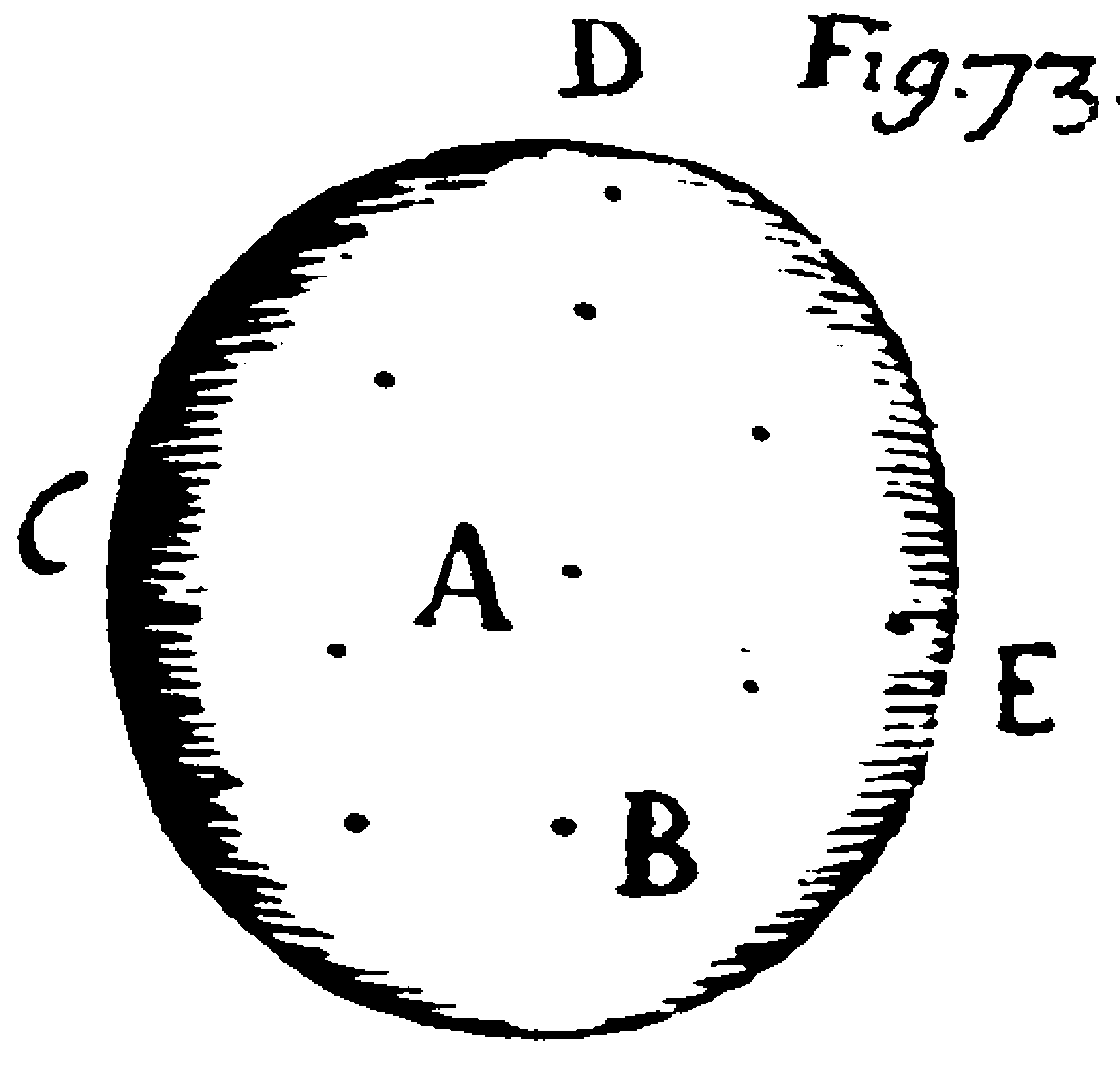

ANd thus much of the Opinion of the Nullibists. Let us now examine the Opinion of the Holenmerians, whose Explication is thus:  Let there be what Body you please, suppose C, D, E, which the Soul or a Spirit may possess and penetrate. The Holenmerians affirm, that the whole Soul or Spirit does occupy and possess the whole Body C, D, E, by its Essence; and that it is also wholly or all of it in every part or point of the said Body C, D, E, as in A, for example, and in B, and the rest of the least parts or points of it. This is a brief and clear Explication of their Opinion.

Let there be what Body you please, suppose C, D, E, which the Soul or a Spirit may possess and penetrate. The Holenmerians affirm, that the whole Soul or Spirit does occupy and possess the whole Body C, D, E, by its Essence; and that it is also wholly or all of it in every part or point of the said Body C, D, E, as in A, for example, and in B, and the rest of the least parts or points of it. This is a brief and clear Explication of their Opinion.

<313> But the Reasons that induce them to embrace it, and so stiffly to maintain it, are these two onely, or at least chiefly, as much as respects the Holenmerism of Spirits. The first is, That whereas they grant that the whole [126] Soul does pervade and possess the whole Body, they thought it would thence follow that the Soul would be divisible, unless they should correct again this Assertion of theirs, by saying, that it was yet so in the whole Body, that it was totally in the mean time in every part thereof: For thus they thought themselves sure, that the Soul could not thence be argued in any sort divisible, or corporeal, but still remain purely spiritual.

Their other Reason is, That from hence it might be easily understood, how the Soul being in the whole Body C, D, E, whatever happens to it in C, or B, it presently perceives it in A; Because the whole Soul being perfectly and entirely as well in C, or B, as in A, it is necessary that after what fashion soever C or B is affected, A should be affected after the same manner; forasmuch as it is entirely and perfectly one and the same thing, viz. the whole Soul, as well in C or B, as in A. And from hence is that vulgar saying in the Schools, That if the Eye were in the Foot, the Soul would see in the Foot.

[127] SECT. XII.

The Examination of the Opinion of the Holenmerians.

BUt now, according to our custome, let us weigh and examine all these things in a free and just Balance. In this therefore that they assert, that the whole Soul is in the whole Body, and is all of it penetrated of the Soul by her Essence, and therefore seem willingly to acknowledge a certain essential amplitude of the Soul; in this, I say, they come near to us, who contend there is a certain Metaphysical and Essential Extension in all Spirits, but such as is ἀμεγέθης καὶ ἀμερὴς, devoid of bulk or parts, as Aristotle defines of his separate substances: For there is no magnitude or bulk which may not be physically divided, nor any parts properly where there is no such division. Whence the Metaphysical Extension of Spirits, is rightly understood not to be capable of either bulk or parts. And in that sence it has no parts, it cannot justly be said to be a Whole. In that therefore we plainly agree with the Holenmerians, that a Soul or Spirit may be said by its Essence to penetrate and possess the whole Body C, D, E; but in this again we differ from them, that we dare not affirm that the whole Spirit [128] or whole Soul does penetrate and possess the said Body, because that which has not parts cannot properly be called a Whole; though I will not over-stiffly contend, but that we may use that word for a more easie explication of our mind, according to that old trite Proverb, Αμαθέστερόν πως εἰπὲ καὶ σαφέστερον λέγε, Speak a little more unlearnedly that thou mayest speak more intelligibly or plainly. But then we are to remember that we do not speak properly, though more accommodately to the vulgar apprehension, but improperly.

But now when the Holenmerians add further, That the whole Soul is in every part or Physical point of the Body D, C, E, in the point A and B,[1] and all the rest of the points of which the Body D, C, E, does consist, that seems an harsh expression to me, and such as may justly be deemed next door to an open Repugnancy and Contradiction: For when they say the whole Soul is in the whole Body D, C, E, if they understand the Essence of the Soul to be commensurate, and as it were equal to the Body D, C, E, and yet at the same time, the whole Soul to be contained within the point A or B, it is manifest that they make one and the same thing many thousand times greater or less than itself at the same time; which is impossible. But if they will affirm, that the essential Amplitude of the Soul is no bigger than what is [129] contained within the Physical point A, or B; but that the Essential Presence of the Soul is diffused through the whole Body D, C, E, the thing will succeed not a jot the better. For while they plainly profess that the whole Soul is in the point A, it is manifest that there remains nothing of the Soul which may be in the point B, which is distant from A: For it is as if one should say, that there is nothing of the Soul which is not included within A; and yet in the same moment of time, that not onely something of the Soul, (which perhaps might be a more gentle Repugnancy) but that the whole Soul is in B, as if the whole Soul were totally and entirely out of itself; which surely is impossible in any singular or individual thing. And as for Universals, they are not Things, but Notions we use in contemplating them.

Again, if the Essential Amplitude of the Soul is no greater than what may be contained within the limits of a Physical point, it cannot extend or exhibit its Essential Presence through the whole Body, unless we imagine in it a stupendious velocity, such as it may be carried with in one moment into all the parts of the Body, and so be present to them: Which when it is so hard to conceive in this scant compages of an humane Body, and in the Soul occupying in one moment every part thereof, What an outragious thing is it, [130] and utterly impossible to apprehend touching that Spirit which perpetually exhibits his Essential Presence to the whole world, and whatever is beyond the world?

To which lastly, you may add that this Hypothesis of the Holenmerians, does necessarily make all Spirits the most minute things that can be conceived: For if the whole Spirit be in every Physical point, it is plain that the Essential Amplitude itself of the Spirit (which the two former Objections supposed) is not bigger than that <314> Physical point in which it is, (which you may call, if you will, a Physical Monad) than which nothing is or can be smaller in universal Nature: Which if you refer to any created Spirit, it cannot but seem very ridiculous; but if to the Majesty and Amplitude of the divine Numen, intolerable, that I may not say plainly reproachful and blasphemous.

SECT. XIII.

A Confutation of the first Reason of the Holenmerians.

BUt now for the Reasons for which the Holenmerians adhere to so absurd an Opinion; verily they are such as can no ways compensate those huge difficulties and repugnancies the Opinion itself labours under. For, for the [131] first, which so solicitously provides for the Indivisibility of Spirits, it seems to me to undertake a charge either Superfluous or Ineffectual. Superfluous, if Extension can be without Divisibility, as it is clearly demonstrated it can, in that infinite immovable Extension distinct from the movable Matter, Enchirid. Metaphys. cap. 6, 7, 8. But Ineffectual, if all Extension be divisible, and the Essential Presence of a Spirit which pervades and is extended through the whole Body C, D, E, may for that very reason be divided; for so the whole Essence which occupies the whole Body C, D, E, will be divided into parts. No by no means, will you say, forasmuch as it is wholly in every part of the Body.

Therefore it will be divided, if I may so speak, into so many Totalities. But what Logical ear can bear a saying so absurd and abhorrent from all reason, that a Whole should not be divided into parts but into Wholes? But you will say at least we shall have this granted us, that an Essential Presence may be distributed or divided according to so many distinctly cited Totalities which occupy at once the whole Body C, D, E, Yes verily, this shall be granted you, after you have demonstrated that a Spirit not bigger than a Physical Monad can occupy in the same instant all the parts of the Body C, D, E; but upon this condition, that you acknowledge not sundry Totalities, but one onely total Essence; though the least that can [132] be imagined, can occupy that whole space, and when there is need, occupy, in an instant, an infinite one: Which the Holenmerians must of necessity hold touching the Divine Essence, because according to their Opinion taken in the second sence, (which pinches the whole Essence of a Spirit into the smallest point) the Divine Essence itself is not bigger than any Physical Monad. From whence it is apparent the three Objections which we brought in the beginning do again recur here, and utterly overwhelm the first reason of the Holenmerians: So that the remedy is far more intolerable than the disease.

SECT. XIV.

A Confutation of the second Reason of the Holenmerians.

ANd truly the other reason which from this Holenmerism of Spirits pretends a more  easie way of conceiving how it comes to pass that the Soul, suppose in A, can perceive what happens to it in C, or B, and altogether in the same circumstances as if it[133]self were perfectly and entirely in C, or B, when yet it is in A; although at first shew this seems very plausible, yet if we look throughly into it, we shall find it far enough from performing what it so fairly promises. For besides that nothing is more difficult or rather impossible to conceive, than that an Essence not bigger than a Physical point should occupy and possess the whole Body of a man at the same instant, this Hypothesis is moreover plainly contrary and repugnant to the very Laws of the Souls Perceptions: For Physicians and Anatomists with one consent profess, that they have found by very solid experiments, that the Soul perceives onely within the Head, and that without the Head there is no perception: Which could by no means be, if the Soul herself were wholly in the point A, and the very self-same Soul again wholly in the point B, and C, nor any where as to Essential Amplitude bigger than a Physical Monad: For hence it would follow, that one and the same thing would both perceive and not perceive at once; That it would perceive this or that Object, and yet perceive nothing at all; which is a perfect contradiction.

easie way of conceiving how it comes to pass that the Soul, suppose in A, can perceive what happens to it in C, or B, and altogether in the same circumstances as if it[133]self were perfectly and entirely in C, or B, when yet it is in A; although at first shew this seems very plausible, yet if we look throughly into it, we shall find it far enough from performing what it so fairly promises. For besides that nothing is more difficult or rather impossible to conceive, than that an Essence not bigger than a Physical point should occupy and possess the whole Body of a man at the same instant, this Hypothesis is moreover plainly contrary and repugnant to the very Laws of the Souls Perceptions: For Physicians and Anatomists with one consent profess, that they have found by very solid experiments, that the Soul perceives onely within the Head, and that without the Head there is no perception: Which could by no means be, if the Soul herself were wholly in the point A, and the very self-same Soul again wholly in the point B, and C, nor any where as to Essential Amplitude bigger than a Physical Monad: For hence it would follow, that one and the same thing would both perceive and not perceive at once; That it would perceive this or that Object, and yet perceive nothing at all; which is a perfect contradiction.

And from hence the falsity of that common saying is detected, That if the Eye was in the Foot, the Soul would see in the Foot; whenas it does not so much as see in those Eyes which [134] it already hath, but somewhere within the Brain. Nor would the Soul by an Eye in the Foot see, unless by fitting Nerves, not unlike the Optick ones, continued from the Foot to the Head and Brain, where the Soul so far as perceptive, inhabiteth. In the other parts of the Body the Functions thereof are onely vital.

Again, such is the nature of some perceptions of the Soul, that they are fitted for the moving of the Body; so that it is manifest that the very self-same thing which perceives, has the power of moving and guiding of it; Which seems impossible to be done by this Soul, which, according to the Opinion of the Holenmerians, exceeds not the amplitude of a small Physical point, as it may appear at first sight to any one whose reason is not blinded with prejudice.

And lastly, If it be lawful for the Mind of man to give her conjectures touching the Immortal Genii, (whether they be in Vehicles, or destitute of Vehicles) and touching their Perceptions and Essential <315> Presences whether invisible or those in which they are said sometimes to appear to mortal men, there is none surely that can admit that any of these things are competible to such a Spirit as the Holenmerians describe. For how can a Metaphysical Monad, that is to say, a Spiritual substance not exceeding a Physical Monad in Ampli[135]tude, fill out an Essential Presence bigger than a Physical Monad, unless it be by a very swift vibration of itself towards all parts; as Boys by a very swift moving of a Fire-stick, make a fiery Circle in the air by that quick motion. But that Spirits, destitute of Vehicles, should have no greater Essential Presence than what is occupied of a naked and unmoved Metaphysical Monad, or exhibited thereby, seems so absonous and ridiculous a spectacle to the Mind of man, that unless he be deprived of all sagacity and sensibility of spirit, he cannot but abhor so idle an Opinion.

And as for those Essential Presences, according to which they sometimes appear to men, at least equalizing humane stature, how can a solitary Metaphysical Monad form so great a part of Air or Æther into humane shape, or govern it being so formed? Or how can it perceive any external Object in this swift motion of itself, and quick vibration, whereby this Metaphysical Monad is understood of the Holenmerians, to be present in all the parts of its Vehicle at once? For there can be no perception of the external Object, unless the Object that is to be perceived act with some stay upon that which perceiveth. Nor if it could be perceived by this Metaphysical Monad thus swiftly moved and vibrated towards all parts at once, would it be seen in one place, but in many places at once, and those, as it may happen, very distant.

[136] SECT. XV.

The egregious falsity of the Opinions of the Holenmerians and Nullibists, as also their uselesness for any Philosophical ends.

BUt verily, I am ashamed to waste so much time in refuting such mere trifles and dotages which indeed are such, (that I mean of the Nullibists, as well as this other of the Holenmerians) that we may very well wonder how such distorted and strained conceits could ever enter into the minds of men, or by what artifice they have so spread themselves in the World; but that the prejudices and enchantments of Superstition and stupid admiration of mens Persons are so strong, that they may utterly blind the minds of men, and charm them into dotage. But if any one, all prejudice and parts-taking being laid aside, will attentively consider the thing as it is, he shall clearly perceive and acknowledge, unless all belief is to be denied to the humane faculties, that the Opinions of the Nullibists and Holenmerians, touching Incorporeal Beings, are miserably false; and not that onely, but as to any Philosophical purpose altogether useless. Forasmuch as out of neither Hypothesis there does appear any greater facility of [137] conceiving how the Mind of man, or any other Spirit, performs those Functions of Perception and of Moving of Bodies, from their being supposed nowhere, than from their being supposed somewhere; or from supposing them wholly in every part of a Body, than from supposing them onely, to occupie the whole Body by an Essential or Metaphysical Extension; but on the contrary, that both the Hypotheses do entangle and involve the Doctrine of Incorporeal Beings with greater Difficulties and Repugnancies.

Wherefore, there being neither Truth nor Usefulness in the Opinions of the Holenmerians and Nullibists, I hope it will offend no man if we send them quite packing from our Philosophations touching an Incorporeal Being or Spirit, in our delivering the true Idea or Notion thereof.

SECT. XVI.

That those that contend that the Notion of a Spirit is so difficult and imperscrutable, do not this because they are of a more sharp and piercing Judgement than others, but of a Genius more rude and plebeian.

NOw I have so successfully removed and dissipated those two vast Mounds of [138] Night and Mistiness, that lay upon the nature of Incorporeal Beings, and obscured it with such gross darkness; it remains that we open and illustrate the true and genuine nature of them in general, and propose such a definition of a Spirit, as will exhibit no difficulty to a mind rightly prepared and freed from prejudice: For the nature of a Spirit is very easily understood, provided one rightly and skilfully shew the way to the Learner, and form to him true Notions of the thing. Insomuch that I have often wondred at the superstitious consternation of mind in those men, (or the profaneness of their tempers and innate aversation from the contemplation of Divine things) who if by chance they hear any one professing that he can with sufficient clearness and distinctness conceive the nature of a Spirit, and communicate the Notion to others, they are presently astartled and amazed at the saying, and straightway accuse the man of intolerable levity or arrogancy, as thinking him to assume so much to himself, and to promise to others, as no humane Wit, furnished with never so much knowledge, can ever perform. And this I understand even of such men who yet readily acknowledge the Existence of Spirits.

But as for those that deny their Existence, whoever professes this skill to them, verily he cannot but appear a man above all measure [139] vain and doting. But I hope that I shall so bring it about, that no man shall appear more stupid and doting, no man more unskilful and ignorant, than he that esteems the clear Notion of a Spirit so hopeless and desperate an attempt; and that I shall plainly detect, that this big and boastful profession of their ignorance in these things does not proceed from hence, that they have any thing more a sharp or discerning Judgment than other mortals, but that they have more gross and weak parts, and a shallower Wit, and such as comes nearest to the superstition and stupidity of the rude vulgar, who easilier fall into admiration and astonishment, than pierce into the reasons and notices of any difficult matter.

SECT. XVII.

The Definition of Body in general, with so clear an Explication thereof, that even they that complain of the obscurity of a Spirit, cannot but confess they perfectly understand the nature of Body.

BUt now for those that do thus despair of any true knowledge of the nature of a Spirit, I would entreat them to try the abilities of their wit in recognizing and throughly considering the nature of Body in general. And [140] let them ingenuously tell me whether they cannot but acknowledge this to be a clear and perspicuous definition thereof, viz. That Body is Substance Material, of itself altogether destitute of all Perception, Life, and Motion. Or thus: Body is a Substance Material coalescent or accruing together into one, by vertue of some other thing, from whence that one by coalition, has or may have Life also, Perception and Motion.

I doubt not but they will readily answer, that they understand all this (as to the terms) clearly and perfectly; nor would they doubt of the truth thereof, but that we deprive Body of all Motion from itself, as also of Union, Life, and Perception. But that it is Substance, that is, a Being subsistent by itself, not a mode of some Being, they cannot but very willingly admit, and that also it is a material Substance compounded of physical Monads, or at least of most minute particles <318> of Matter, into which it is divisible; and because of their Impenetrability, impenetrable by any other Body. So that the Essential and Positive difference of a Body is, that it be impenetrable, and Physically divisible into parts: But that it is extended, that immediately belongs to it as it is a Being. Nor is there any reason why they should doubt of the other part of the Differentia, whenas it is solidly and fully proved in Philosophie, That Matter of its own nature, or in itself, is [141] endued with no Perception, Life, nor Motion. And besides, we are to remember that we here do not treat of the Existence of things, but of their intelligible Notion and Essence.

SECT. XVIII.

The perfect Definition of a Spirit, with a full Explication of its Nature through all Degrees.

ANd if the Notion or Essence is so easily understood in nature Corporeal or Body, I do not see but in the Species immediately opposite to Body, viz. Spirit, there may be found the same facility of being understood. Let us try therefore, and from the Law of Opposites let us define a Spirit, an Immaterial Substance intrinsecally endued with Life and the faculty of Motion. This slender and brief Definition that thus easily flows without any noise, does comprehend in general the whole nature of a Spirit; Which lest by reason of its exility and brevity it may prove less perceptible to the Understanding, as a Spirit is to the sight, I will subjoyn a more full Explication, that it may appear to all, that this Definition of a Spirit is nothing inferiour to the Definition of a Body as to clearness and perspicuity. And that by this method which we [142] now fall upon, a full and perfect knowledge and understanding of the nature of a Spirit may be attained to.

Go to therefore, let us take notice through all the degrees of the Definitum, or Thing defined, what precise and immediate properties each of them contain, from whence at length a most distinct and perfect knowledge of the whole Definitum will discover itself. Let us begin then from the top of all, and first let us take notice that a Spirit is Ens, or a Being, and from this very same that it is a Being; that it is also One, that it is True, and that it is Good; which are the three acknowledged Properties of Ens in Metaphysicks, that it exists sometime, and somewhere, and is in some sort extended, as is shewn Enchirid. Metaphys. cap. 2. sect. 10. which three latter terms are plain of themselves. And as for the three former, that One signifies undistinguished or undivided in and from itself, but divided or distinguished from all other, and that True denotes the answerableness of the thing to its own proper Idea, and implies right Matter and Form duely conjoyned, and that lastly Good respects the fitness for the end in a large sence, so that it will take in that saying of Theologers, That God is his own End, are things vulgarly known to Logicians and Metaphysicians. That these Six are the immediate affections of Being, as Being is made apparent in the above-cited En[143]chiridion Metaphysicum; nor is it requisite to repeat the same things here. Now every Being is either Substance, or the Mode of Substance, which some call Accident: But that a Spirit is not an Accident or Mode of Substance, all in a manner profess; and it is demonstrable from manifold Arguments, that there are Spirits which are no such Accidents or Modes; Which is made good in the said Enchiridion and other Treatises of Dr. H. M.

Wherefore the second Essential degree of a Spirit is, that it is Substance. From whence it is understood to subsist by itself, nor to want any other thing as a Subject (in which it may inhere, or of which it may be the Mode or Accident) for its subsisting or existing.

The third and last Essential degree is, that it is Immaterial, according to which it immediately belongs to it, that it be a Being not onely One, but one by itself, or of its own intimate nature, and not by another; that is, That, though as it is a Being it is in some sort extended, yet it is utterly Indivisible and Indiscerpible into real Physical parts. And moreover, That it can penetrate the Matter, and (which the Matter cannot do) penetrate things of its own kind; that is, pass through Spiritual Substances. In which two Essential Attributes (as it ought to be in every perfect and legitimate Distribution of any Genius) it is fully and accurately contrary to its opposite Species, [144] namely, to Body. As also in those immediate Properties whereby it is understood to have Life intrinsecally in itself, and the faculty of moving; which in some sence is true in all Spirits whatsoever, for-asmuch as Life is either Vegetative, Sensitive, or Intellectual. One whereof at least every Spiritual Substance hath: as also the faculty of moving; insomuch that every Spirit either moves itself by itself, or the Matter, or both, or at least the Matter either mediately or immediately; or lasty, both ways. For so all things moved are moved by God, he being the Fountain of all Life and Motion.

SECT. XIX.

That from hence that the Definition of a Body is perspicuous, the Definition of a Spirit is also necessarily perspicuous.

WHerefore I dare here appeal to the Judgment and Conscience of any one that is not altogether illiterate and of a dull and obtuse Wit, whether this Notion or Definition of a Spirit in general, is not as intelligible and perspicuous, is not as clear and every way distinct as the Idea or Notion of a Body, or of any thing else whatsoever which the mind of man can contemplate in the whole compass [145] of Nature. And whether he cannot as easily or rather with the same pains apprehend the nature of a Spirit as of Body, forasmuch as they both agree in the immediate Genus to them, to wit Substance. And the Differentiæ do illustrate one another by their mutual opposition; insomuch that it is impossible that one should understand what is Material Substance, but he must therewith presently understand what Immaterial Substance is, or what it is not to have Life and Motion of itself, but he must straitway perceive what it is to have both in itself, or to be able to communicate them to others.

SECT. XX.

Four Objections which from the perspicuity of the terms of the Definition of a SPIRIT infer the Repugnancy of them one to another.

NOr can I divine what may be here opposed, unless haply they may alledge such things as these, That although they cannot deny but that all the terms of the Definition and Explication of them, are sufficiently intelligible, if they be considered single, yet if they be compared one with another they will mutually destroy one another. For this Extension which is mingled with, or inserted into [146] the nature of a Spirit, seems to take away the Penetrability and Indivisibility thereof, as also its faculty of thinking, as its Penetrability likewise takes away its power of moving any Bodies.

<319> I. First, Extension takes away Penetrability; because if one Extension penetrate another, of necessity either one of them is destroyed, or two equal Amplitudes entirely penetrating one another, are no bigger than either one of them taken single, because they are closed within the same limits.

II. Secondly, It takes away Indivisibility; because whatsoever is extended has partes extra partes, one part out of another, and therefore is Divisible: For neither would it have parts, unless it could be divided into them. To which you may further add, that forasmuch as the parts are substantial, nor depend one of another, it is clearly manifest that at least by the Divine Power they may be separate, and subsist separate one from another.

III. Thirdly, Extension deprives a Spirit of the faculty of thinking, as depressing it down into the same order that Bodies are. And that there is no reason why an extended Spirit should be more capable of Perception than Matter that is extended.

IV. Lastly, Penetrability renders a Spirit unable to move Matter; because, whenas by reason of this Penetrability it so easily slides [147] through the Matter, it cannot conveniently be united with the Matter whereby it may move the same: For without some union or inherency (a Spirit being destitute of all Impenetrability) 'tis impossible it should protrude the Matter towards any place.

The sum of which Four difficulties tends to this, that we may understand, that though this Idea or Notion of a Spirit which we have exhibited be sufficiently plain and explicate, and may be easily understood; yet from the very perspicuity of the thing itself, it abundantly appears, that it is not the Idea of any possible thing, and much less of a thing really existing, whenas the parts thereof are so manifestly repugnant one to another.

SECT. XXI.

An Answer to the first of the Four Objections.

I. BUt against as well the Nullibists as the Hobbians, who both of them contend that Extension and Matter is one and the same thing, we will prove that the Notion or Idea of a Spirit which we have produced, is a Notion of a thing possible. And as for the Nullibists, who think we so much indulge to corporeal Imagination in this our Opinion of the Extension of Spirits, I hope on the contrary, [148] that I shall shew that it is onely from hence, that the Hobbians and Nullibists have taken all Amplitude from Spirits, because their Imagination is not sufficiently defecated and depurated from the filth and unclean tinctures of Corporeity, or rather that they have their Mind over-much addicted and enslaved to Material things, and so disordered, that she knows not how to expedite herself from gross Corporeal Phantasms.

From which Fountain have sprung all those difficulties whereby they endeavour to overwhelm this our Notion of a Spirit; as we shall manifestly demonstrate by going through them all, and carefully perpending each of them. For it is to be imputed to their gross Imagination, That from hence that two equal Amplitudes penetrate one another throughout, they conclude that either one of them must therewith perish, or that they being both conjoyned together, are no bigger than either one of them taken single. For this comes from hence that their mind is so illaqueated or limetwigged, as it were, with the Idea's and Properties of corporeal things, that they cannot but infect those things also which have nothing corporeal in them with this material Tincture and Contagion, and so altogether confound this Metaphysical Extension with that Extension which is Physical. I say, from this disease it is that the sight of their mind is become so dull [149] and obtuse, that they are not able to divide that common Attribute of a Being, I mean Extension Metaphysical from special Extension and Material, and assign to Spirits their proper Extension, and leave to Matter hers. Nor according to that known method, whether Logical or Metaphysical, by intellectual Abstraction prescind the Generical nature of Extension from the abovesaid Species or kinds thereof. Nor lastly, (which is another sign of their obtuseness and dulness) is their mind able to penetrate with that Spiritual Extension into the Extension Material; but like a stupid Beast stands lowing without, as if the mind itself were become wholly corporeal; and if any thing enter they believe it perishes rather and is annihilated, than that two things can at the same time coexist together in the same Ubi. Which are Symptomes of a mind desperately sick of this Corporeal Malady of Imagination, and not sufficiently accustomed or exercised in the free Operations of the Intellectual Powers.

And that also proceeds from the same source, That supposing two Extensions penetrating one another, and adequately occupying the same Ubi, they thus conjoyned are conceived not to be greater than either one of them taken by itself. For the reason of this mistake is, that the Mind incrassated and swayed down by the Imagination, cannot together with the [150] Spiritual Extension penetrate into the Material, and follow it throughout, but onely places itself hard by, and stands without like a gross stupid thing, and altogether Corporeal. For if she could but, with the Spiritual Extension, insinuate herself into the Material, and so conceive them both together as two really distinct Extensions, <320> it is impossible but that she should therewith conceive them so conjoyned into one Ubi, to be notwithstanding not a jot less than when they are separated and occupy an Ubi as big again: For the Extension in neither of them is diminished, but their Situation onely changed. As it also sometimes comes to pass in one and the same Extension of some particular Spirits which can dilate and contract their Amplitude into a greater or lesser Ubi without any Augmentation or Diminution of their Extension, but onely by the expansion and retraction of it into another site.

[151] SECT. XXII.

That besides those THREE Dimensions which belong to all extended things, a FOURTH also is to be admitted, which belongs properly to SPIRITS.

ANd that I may not dissemble or conceal any thing, Although all Material things, considered in themselves, have three Dimensions onely; yet there must be admitted in Nature a Fourth, which fitly enough, I think, may be called Essential Spissitude; Which, though it most properly appertains to those Spirits which can contract their Extension into a less Ubi; yet by an easie Analogie it may be referred also to Spirits penetrating as well the Matter as mutually one another: So that where-ever there are more Essences than one, or more of the same Essence in the same Ubi than is adequate to the Amplitude thereof, there this Fourth Dimension is to be acknowledged, which we call Essential Spissitude.

Which assuredly involves no greater repugnancy than what may seem at first view, to him that considers the thing less attentively, to be in the other three Dimensions. Namely, unless one would conceive that a piece of Wax stretched out, suppose, to the length of an Eln, [152] and afterwards rolled together into the form of a Globe, loses something of its former Extension, by this its conglobation, he must confess that a Spirit, neither by the contraction of itself into a less space has lost any thing of its Extension or Essence, but as in the abovesaid Wax the diminution of its Longitude is compensated with the augmentation of its Latitude and Profundity; so in a Spirit contracting itself, that in like manner its Longitude, Latitude, and Profundity being lessened, are compensated by Essential Spissitude, which the Spirit acquires by this contraction of itself.

And in both cases we are to remember that the Site is onely changed, but that the Essence and Extension are not at all impaired.

Verily these things by me are so perfectly every way perceived, so certain and tried, that I dare appeal to the mind of any one which is free from the morbid prejudices of Imagination, and challenge him to trie the strength of his Intellectuals, whether he does not clearly perceive the thing to be so as I have defined, and that two equal Extensions, adequately occupying the very same Ubi, be not twice as great as either of them alone, and that they are not closed with the same terms as the Imagination falsly suggests, but onely with equal. [153] Nor is there any need to heap up more words for the solving this first difficulty; whenas what has been briefly said already abundantly sufficeth for the penetrating their understanding who are prepossest with no prejudice: But for the piercing of theirs who are blinded with prejudices, infinite will not suffice.

SECT. XXIII.

An Answer to the second Objection, where the fundamental Errour of the Nullibists, viz. That whatsoever is extended is the Object of Imagination, is taken notice of.

II. LEt us try now if we can dispatch the second difficulty with like success, and see if it be not wholly to be ascribed to Imagination, that an Indiscerpible Extension seems to involve in it any contradiction. As if there could be no Extension which has not parts real and properly so called into which it may be actually divided. viz. for this reason, that that onely is extended which has partes extra partes, which being substantial, may be separated one from another, and thus separate subsist. This is the summary account of this difficulty, which nothing but corrupt Imagination supporteth.

[154] Now the first source or Fountain of this errour of the Nullibists, is this; That they make every thing that is extended the Object of the Imagination, and every Object of the Imagination Corporeal. The latter whereof undoubtedly is true, if it be taken in a right sence; namely, if they understand such a perception as is either simply and adequately drawn from external Objects; or by increasing, diminishing, transposing, or transforming of parts (as in Chimæra’s and Hippocentaurs) is composed of the same. I acknowledge all these Idea's, as they were sometime some way Objects of Sensation, so to be the genuine Objects of Imagination, and the perception of these to be rightly termed the operation of Fancie, and that all these things that are thus represented, necessarily are to be look'd upon as corporeal, and consequently as actually divisible.

But that all perception of Extension is such Imagination, that I confidently deny. Forasmuch as there is an Idea of infinite Extension drawn or taken in from no external sense, but is natural and Essential to the very faculty of perceiving; Which the mind can by no means pluck out of herself, nor cast it away from her; but if she will rouze herself up, and by earnest and attentive thinking, fix her animadversion thereon, she will be constrained, whether she will or no, to acknowledge, that [155] although the whole matter of the world were exterminated out of the Universe, there would notwithstanding remain a certain subtile and immaterial Extension which has no agreement with that other Material one, in any thing, saving that it is extended, as being such that it neither falls under sense, nor is impenetrable, nor can be moved, nor discerped into parts; and that this <321> Idea is not onely possible, but necessary, and such as we do not at our pleasure feign and invent, but do find it to be so innate and ingrafted in our mind, that we cannot by any force or artifice remove it thence. Which is a most certain demonstration that all Perception of Extension is not Imagination properly so called.

Which in my Opinion ought to be esteemed one of the chiefest and most fundamental Errours of the Nullibists, and to which especially this difficulty is to be referred touching an Indiscerpible Extension. For we see they confess their own guilt, namely, that their Mind is so corrupted by their Imagination, and so immersed into it, that they can use no other faculty in the contemplation of any extended thing. And therefore when they make use of their Imagination instead of their Intellect in contemplating of it, they necessarily look upon it as an Object of Imagination; that is, as a corporeal thing, and discerpible into parts. For, as I noted above, the sight of their mind by reason [156] of this Morbus ὑλοειδὴς, this materious Disease, if I may so speak, is made so heavie and dull, that it cannot distinguish any Extension from that of Matter, as allowing it to appertain to another kind, nor by Logical or Metaphysical Abstraction prescind it from either.

SECT. XXIV.

That Extension as such includes in it neither Divisibility nor Impenetrability, neither Indivisibility nor Penetrability, but is indifferent to either two of those properties.

ANd from hence it is that because a thing is extended they presently imagine that it has partes extra partes, and is not Ens unum per se & non per aliud, a Being one by itself, and not by vertue of another, but so framed from the juxtaposition of parts. Whenas the Idea of Extension precisely considered in itself includes no such thing, but onely a trinal Distance or solid Amplitude, that is to say, not linear onely and superficiary, (if we may here use those terms which properly belong to magnitude Mathematical) but every way running out and reaching towards every part. This Amplitude surely, and nothing beside, does this bare and simple Extension include, [157] not Penetrability nor Impenetrability, not Divisibility nor yet Indivisibility, but to either affections or properties, or if you will Essential Differences, namely, to Divisibility and Impenetrability, or to Penetrability and Indivisibility, if considered in itself, is it altogether indifferent, and may be determined to either two of them.

Wherefore, whereas we acknowledge that there is a certain Extension namely Material, which is endued with so stout and invincible an Ἀντιτυπία or Impenetrability, that it necessarily and by an insuperable Renitencie expels and excludes all other Matter that occurs and attempts to penetrate it, nor suffers it at all to enter, although in the simple Idea of Extension, this marvellous virtue of it is not contained, but plainly omitted, as not at all belonging thereto immediately and of itself; why may we not as easily conceive that another Extension, namely, an Immaterial one, though Extension in itself include no such thing, is of such a nature, that it cannot by any other thing whether Material or Immaterial be discerped into parts; but by an indissoluble necessary and essential Tie be so united and held together with itself, that although it can penetrate all things and be penetrated by all things, yet nothing can so insinuate itself into it as to disjoyn any thing of its Essence any where, or perforate it or make any hole [158] or Pore in it? that is, that I may speak briefly, What hinders but there may be a Being that is immediately One of its own nature, and not held together into one by vertue of some other, either Quality or Substance? although every Being as a Being is extended, because Extension in its precise Notion does not include any Physical Division, but the Mind infected with corporeal Imagination, does falsly and unskilfully feign it to be necessarily there.

SECT. XXV.

That every thing that is extended has not parts Physically discerpible, though Logically or Intellectually divisible.

FOr it is nothing which the Nullibists here alledge, while they say, That all Extension inferreth parts, and all parts Division. For besides that the first is false, forasmuch as Ens unum per se, a Being one of itself or of its own immediate nature, although extended yet includes no parts in its Idea, but is conceived according to its proper Essence as a thing as simple as may be, and therefore compounded of no parts: We answer moreover, that it is not at all prejudicial to our cause though we should grant that this Metaphysical Extension of Spirits is also divisible, but Logically onely, [159] not Physically; that is to say, is not discerpible. But that one should adjoyn a Physical divisibility to such an Extension, surely that must necessarily proceed from the impotencie of his Imagination, which his Mind cannot curb, nor separate herself from the dreggs and corporeal foulnesses thereof; and hence it is that she tinctures and infects this pure and Spiritual Extension with Corporeal Properties. But that an extended thing may be divided Logically or Intellectually, when in the mean time it can by no means be discerped, it sufficiently appears from hence, That a Physical Monad which has some Amplitude, though the least that possible can be, is conceived thus to be divided in a Line consisting of any uneven number of Monads, which notwithstanding the Intellect divides into two equal parts. And verily in a Metaphysical Monad, such as the Holenmerians conceit the Mind of man to be, and to possess in the mean time and occupie the whole Body, there may be here again made a Logical Distribution, suppose, è subjectis, as they call it, so far forth as this Metaphysical Monad, or Soul of the Holenmerians is conceived to possess the Head, or Trunk, or Limbs of the Body. And yet no man <322> is so delirant as to think that it follows from thence, that such a Soul may be discerped into so many parts, and that the parts so discerped may subsist by themselves.

[160] SECT. XXVI.

An Answer to the latter part of the Second Objection, which inferreth the separabilitie of the parts of a Substantial Extensum, from the said parts being Substantial and independent one of another.

FRom which a sufficiently fit and accommodate Answer may be fetched to the latter part of this difficulty, namely, to that, which because the parts of Substance are Substantial and independent one of another, and subsisting by themselves (as being Substances) would infer that they can be discerped, at least by the Divine Power, and disjoyned, and being so disjoyned, subsist by themselves. Which I confess to be the chief edge or sting of the whole difficulty, and yet such as I hope I shall with ease file off or blunt. For first, I deny that in a thing that is absolutely One and Simple as a Spirit is, there are any Physical parts, or parts properly so called, but that they are onely falsly feigned and fancied in it, by the impure Imagination. But that the Mind it self being sufficiently defecated and purged from the impure dreggs of Fancie, although from some extrinsecal respect she may consider a Spirit as having parts, yet at the very [161] same time does she in herself, with close attention, observe and note, that such an Extension of itself has none. And therefore whenas it has no parts it is plain it has no substantial parts, nor independent one of another, nor subsistent of themselves.